By R. Harrison Wolcott

In three short years, Yun Gee, the young Chinese artist, who forsook academies and teachers and took to the streets of San Francisco to paint, rose to a place of prominence in the rank and file of the forty thousand artists said to be in Paris. The Paris years have been full of work. Mr. Gee returned recently to America, leaving behind him thirty paintings on exhibit in the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery, Paris.

One wonders what dynamic force drove so young an artist to the top, through such a galaxy of painters, in a city where art is guarded with jealous care. First of all, he was endowed with indefatigable industry. The little, slim hands that were so soft and pliant when he left America three years ago, are larger now, and stronger. He has toiled early and late, and felt no sacrifice too great for art’s sake. There must have been something unusual about him or his work.

When he was only fifteen years old, Yun Gee came from Canton to San Francisco. For a while, he studied at the Academie of Art of California. He is not a school man; he is original, a free thinker, and soon he found himself out of sympathy with the spirit of the academy and left. The next chapter in his young life was a friendship with Oldfield, a renowned painter among the modernistic group, then recently returned from Paris. Inspired by Oldfield, Yun gathered about him a coterie of young artists and founded the School of the Revolution in Art on Montgomery Street, San Francisco.

At its very first exhibition, the school proved a success, attracting wide public interest and approval. Yun alone sold then pictures at this first exhibit.

Youth clings to Yun as though loathe to leave this apostle of art. He was born Feb. 22, 1906, in Canton, China. Very lightly his twenty-four years sit upon him – a heavy mass of long black hair, big sparkling brown eyes, a ghost of a mustache and beard that he secretly believes adds age and dignity, a little, slight figure whose clothes seem too large – all that is the material side of Yun. It is the spirit that animates that delicate frame that is mighty, forging ahead regardless of circumstances or interruptions. Quite overshadowing his youthful look there surrounds him the aura of a pilgrim of the earth, such as he of whom Edwin Markham sings:

. . . Comes a pilgrim of the universe,

Out of the mystery that was before

The world, out of the wonder of old stars

Far roads have felt his feet, forgotten wells

Have glassed his beauty bending down to drink.

His paintings are philosophical poems on canvas. A worn, thumbed copy of the Analects of Confucius came out of the top tray of his old, crowded trunk, with the inside of its lid carved full of names of distinguished writers and poets and artists, all his friends. He feels the sympathy and kinship with rock and bird and sea that Laotze felt. “One’s love of one’s self,” is the theme of one of these philosophical paintings. In explaining it, he said:

“To really love the universe, you must first love yourself,” a statement of truth that unfolds in the mind with thought.

One is impressed with the range and significance of his ideas rather than his technique. His technique is strongly marked with the influence of cubists and the futurists, while the unusual quality in the work of this artist is his ability to sense world movements. He feels the rhythm of world movements and transfers them to canvas with refreshing and modern touch. He also has unusual ability to revivify old themes.

His “Soldiers of Christ,” purchased by a noted lover of art in Paris, most vividly illustrates his sense of world tendencies. It is a tiny canvas hardly more than a foot square, painted while he was still in San Francisco. The import of this picture grows with the passing of days. A great white cross, that appears to emit light, almost fills the entire canvas. Under the very shadow of the cross, trudge soldiers, heavily laden, bending under their load. Not one goes with unlifted face, or seems to be aware he is passing at the very foot of the cross. The conception almost overwhelms one, until you cry out:

“Yun, what do you mean by this?”

Puffing away at his pipe he made reply:

“The Cross of Christ is the only light in the world today and men are unmindful of it.” With a stroke of his brush he has painted the greatest tragedy of the Twentieth Century.

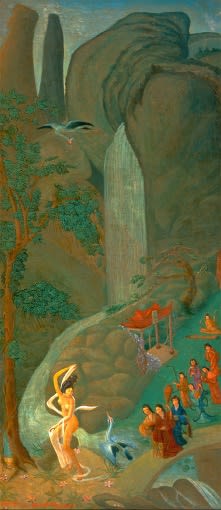

Yang Kwei Fei At Her Bath

Yang Kwei Fei At Her Bath

1929

Before he left Paris, the French republic requested Mr. Gee to present to France his painting “Yang Kuei Fei at the Bath.” Wounded by the treatment the French have in the last few months awarded Chinese in Paris, Mr. Gee declined the honor. The original of this painting hangs in the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery.

Since Mahatma Gandhi marched to the sea and made salt, and his doctrine of non-violence and civil disobedience have become a fact to be reckoned with, the French, never sympathetic with the Chinese, and especially Chinese art, have become more and more aware of the Chinese living in France. Vexed at the spread in Indo-China of Gandhi’s doctrine, which has seriously interfered with her tax income, France, a nation that hitherto prided herself in her tolerance, has become intolerant. Keenly sensitive to this, Mr. Gee found himself weary of the carping of the Old World.

Confucius

1929

Perhaps the greatest of Mr. Gee’s paintings is his “Confucius.” It bids fair to live and be remembered, for it has plumbed profound depths of human relationship. It is the picture of a man who walked with God, like all the great religious teachers of the world.

What a far cry from those exquisite paintings of the old Chinese masters, huddled together without semblance of order, without continuity of subject matter, behind a common piece of white string in the palaces of Peiking, that now serve as temporary storehouse and museum, to Yun Gee with his revolutionary ideas on art, and his blending the old with new. For in the same painting will be an old theme expressed by a combination of cubist strokes and the delicate traceries so well known in Chinese art.

Past many a Kuomintang soldier, standing silently by with fixed bayonets, like so many bronze statues, I peered last summer in an attempt to view more adequately the priceless art treasures of China’s former glory. Did those silent soldiers know, I wondered to myself, looking at their young faces, for few of them were out of their teens, that behind that fragile white string, stood, resting on the floor, one of the most exquisite paintings of all time, painted not with a brush but with the artist’s elongated thumb nail?

In Yun Gee, combines this background of the art of the old Chinese masters whose matchless work awakens inspiration and reverence in all those who truly know them. He is a part of the new China that seeks co-operation with the West, while yet retaining all that is best in their own civilization. He is a part of that new movement, stirring now all over the earth, known as the Youth Movement. In his exhibition in New York this fall, Mr. Gee will bring an interpretation of China’s philosophy and culture that even a novice in a study of the East can understand.