Through the Eyes of a Dandy: Sanyu's Hidden Blossoms

Through the Eyes of a Dandy: Sanyu's Hidden Blossoms

- Overview

- Press Release

- Installation Shots

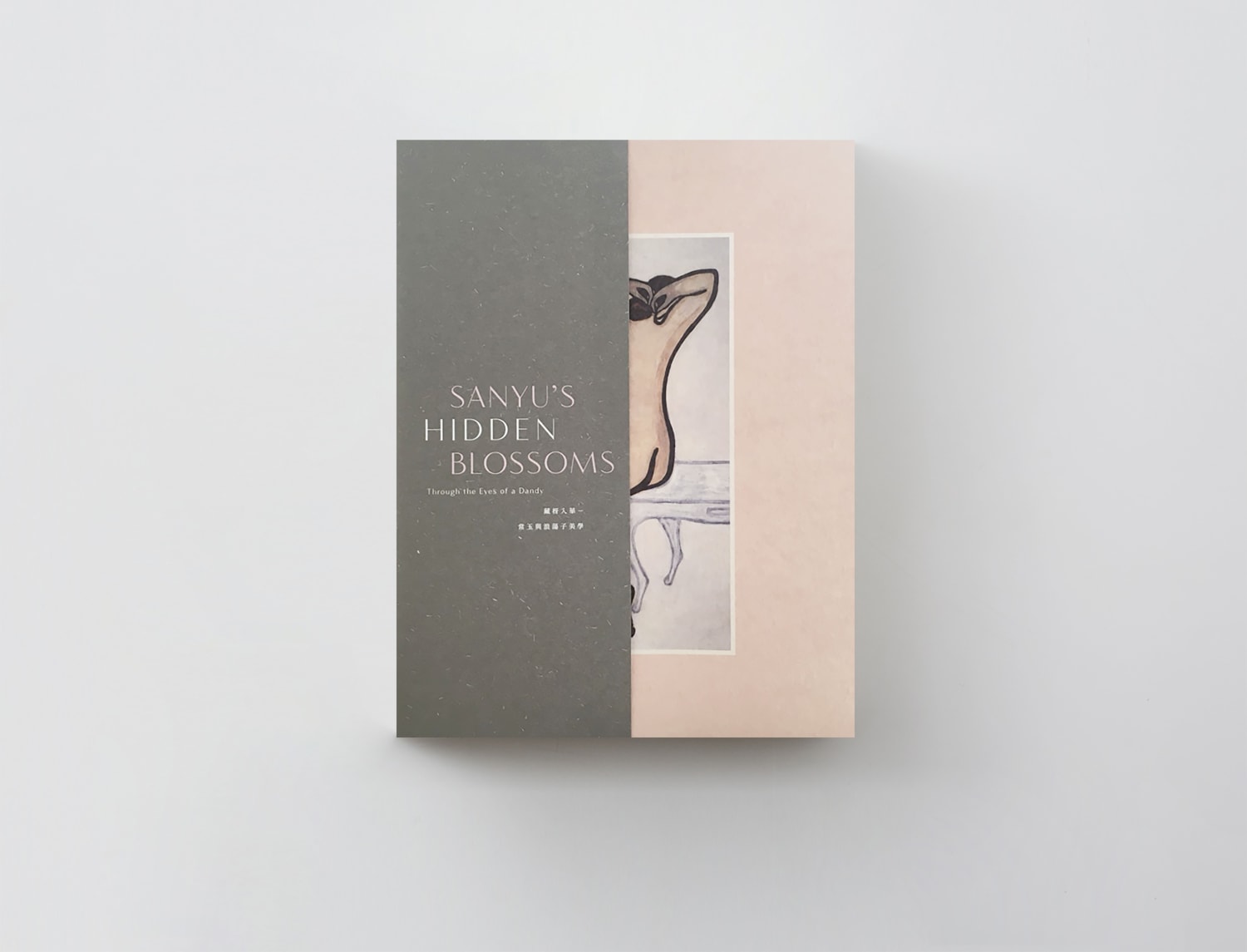

- Publications

- Videos

-

Share

- X

- Tumblr

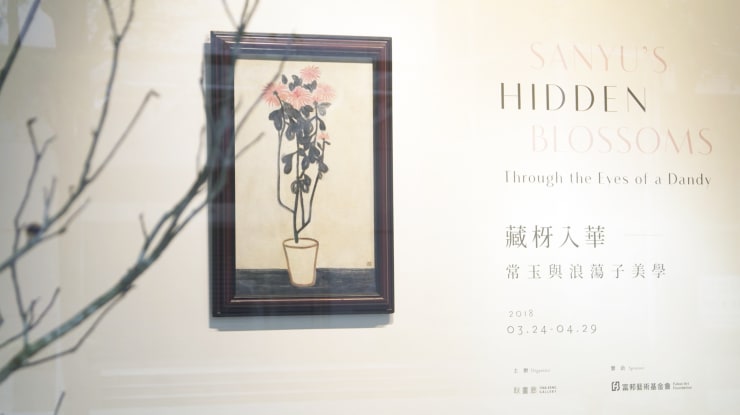

13 March 2018 – Tina Keng Gallery, a leading gallery dedicated to promoting works by Asian classical masters, is delighted to present Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandy, opening on March 24.

Comprising of around forty works of the Chinese modern master, this exhibition will focus on Sanyu’s work that were created between the 1930s and 1940s, with a selection of the last work of his. Formerly known as Lin & Keng Gallery, the Taipei-based Tina Keng Gallery was established in 1992 and began its long representation of the artist with Sanyu–Yun Gee Joint Exhibition: The Nostalgia of Two Wanderersin 1993, one year after opening. Solely curated by its founder, Tina Keng, the gallery subsequently held six other solo exhibitions of Sanyu over last 25 years in 1997, 1998, 2001, 2010, and 2013. Organised by young curator Hsu Fong-Ray, Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandyis the gallery’s latest undertaking to celebrate the legacy of Sanyu.

“I took my first visit to Paris about thirty years ago. This is when I first discovered Sanyu’s work, I was instantly taken by his hand and style. Through curating the past six exhibitions at our gallery, I have come to appreciate the interrelationship between Eastern and Western painting and concepts that are infused in his work. As one of the oldest members in the Taiwanese art community, we are dedicated to nurture and support the new generation of artistic and curatorial talents. For this exhibition, it is particularly exciting to work with the talented curator Hsu Fong-Ray, who has the ability to relate contemporary aesthetics in the work of Sanyu that transcend generations.” Tina Keng, founder of the gallery commented.

Sanyu’s Hidden Blossomschronicles from the artist’s nascent beginnings at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, where he honed his painting skills, to the very last painting he produced before he passed away in 1966. Evoking the Parisian milieu where artistic greats gathered, the exhibition consists of precious works on paper that came into being at la Grande Chaumière, as well as a constellation of oil works between the 1930s and 1940s from what is known as the ‘Pink Period’, characterized by a palette of white, black, and pink. In addition to the sgraffito technique he used to outline his subject, this particular body of work attests to Sanyu's dexterous application of feibai, a drybrush technique in Chinese calligraphy that spares out the white ground in streaks, to create varying layers in the seemingly monotone background. Also on view is a series of drawings of the female nude that once struck famed Chinese poet Xu Zhimo as having “cosmic thighs,” and exquisite works loaned from the Fubon Art Foundation that make their appearance for the first time in twenty years.

Sanyu moved to Paris in 1920s when France was regarded as the center of the Années folles (“crazy years” in French) — a period of liberation, creativity, and cultural flourishing in the years following the First World War. “The artists who drifted toward Paris at the turn of the 20thcentury immersed themselves in the crowd and led a modern life. They were the so-called “dandies” in this golden era, who much like a mirror, reflect the diversity of the times, the city, and the people. Spearheading Chinese modern art, these artists navigated the treacherous global currents in search of ways that linked tradition and modernity, with a keen self-awareness as they engaged in the practice of cultural interpretation. Standing at the forefront was Sanyu.” Hsu Fong-Ray, exhibition curator explained.

From Sanyu’s experimentation with techniques to his practice of artistic styles, we can ultimately see a cross-cultural vocabulary of aesthetics and the remnants of modern history in Sanyu’s work. As the artist once said, "The paintings of Europe can be described as an elaborate meal, consisting of barbecue, fried foods, and meat of all kinds. My work is akin to vegetables, fruit, or salad, which helps shape and change the way people appreciate paintings." Treading the line between Western modernity and cultural tradition, Sanyu bore witness to a burgeoning new era, and embodied the dandy aesthetics in a cross-cultural modern milieu. His artistic expression that amalgamates the disparate values and aesthetics of the East and the West underscores not only Sanyu’s inclusiveness, but also his compromise and reinvention in shaping his aesthetic vocabulary. There is a profound creative spirit in Sanyu's work, transcending cultural boundaries, elitism, and popular culture, allowing us a chance to grasp the poetics in aesthetics and history.

Europe and the United States at the turn of the 20thcentury were the epicenters of capitalism as well as leaders at the forefront of global trends in the charge toward modernization. While other regions were still grappling with the agonizing choice between modernity and tradition, the foundations of modernity had been laid in Western Europe and North America. However, while Europe and the United States enjoyed the economic boom resulting from this industrial civilization, capitalist systems abruptly collapsed. The 1929 financial crisis made it difficult for the capitalist system to continue functioning. Fierce confrontations between socialism and capitalism quickly surfaced, becoming a key source of conflicts in modern times. Vast discrepancies in the judgment and development in modernization occurred between advanced and developing nations, which were further manifested in their cultural development.

In the years following the First World War, France was regarded as the center of the Années folles (“crazy years” in French) — a period of liberation, creativity, and cultural flourishing. Up until the Great Depression that began in 1929, the entire society was in anticipation of the arrival of a brand new era, with a carpe diem attitude. Paris in those days was the cradle of modern art. An atmosphere of creativity and romance permeated the city, from Montmartre to the Left Bank, from bookstalls to cafés and taverns, seeping into every corner, thanks to a group of wandering artists who gathered in Paris. Living in Paris, they sought to realize their own artistic practices, while also forging their identities in this environment that transcended cultural barriers. Among them was Sanyu, who came from China.

A Dandy Wandering Through the Era

At the time, the École de Paris was not a specific school of painting, but a unique milieu created by artists who gathered in Montmartre and Montparnasse. Consisting mainly of foreigners from outside of France, they were the Lost Generation who lived through the First World War, and regarded the world around them with a sense of skepticism and an impulse to explore. They had elegant sartorial taste, with an air of intellectualism, seemingly at leisure but with a sharp sense of observation as they strolled through the city streets. They might have appeared nonchalant, but they regarded art making as their sole purpose. In actuality, this aimless drifting reflected the tense relationship between modern people and their times and society. Hence the dramatic contrast between these vagabonds and the profit-driven modern men and women they brushed shoulders with, even though they might have shared similar fashion taste. These people embodied the dandy in French author Charles Pierre Baudelaire’s Le Peintre de la vie moderne, who was subsequently described in French philosopher Michel Foucault’s cultural theory thus, “To be modern is not to accept oneself as one is in the flux of passing moments; it is to take oneself as object of a complex and difficult elaboration: what Baudelaire, in the vocabulary of his day, calls dandysme.”

The artists who drifted toward Paris at the turn of the 20thcentury, specifically the artists from developing nations who encountered firsthand Western modernization and for whom this became their lifestyle, immersed themselves in the crowd and led a modern life. But unlike the modern men and women propelled by sensuous pleasures, these artists possessed mental acuity and persistence in art making, never losing themselves. They were the so-called “dandies.” It is easy to criticize the dandy for their worldly vanity and cynicism, who perhaps seemed worthless to society; but the “dandy” in this text refers to a group of urban dwellers, narrowly defined, who were always cultivating a sense of character and aesthetics to satisfy their own passion for art, riding the tides of modern development. The dandy was a symbol of the avant-garde at that time, shouldering the burden of modernization, and finally becoming a proponent of modernity. The other parts of the world were, too, undergoing a drastic change: imperialism had just ended in China after the 1911 Revolution and the May Fourth Movement, ushering a new era with much still to accomplish. This spurred a demand for change among the youth in the developing nation. As they faced the clash between traditional culture and Western civilization, these cultural workers who left China to pursue studies in the West became the first generation of cultural elites to encounter modernization. They navigated the treacherous global currents in search of ways that linked tradition and modernity, with a keen self-awareness as they engaged in the practice of cultural interpretation. And standing at the forefront of Chinese modern art was Sanyu.

Author Peng Hsiao-Yen’s book Dandyism and Transcultural Modernity (2012) chronicles the influence of dandyism throughout literature, and delves into the dandy aesthetics in relation to characters, concepts, and texts as the trend migrated to Japan and Shanghai from its origins in France, traversing European and Asian cultures. Inherent in dandyism was the creative transformation that took place in the transcultural space, and the sauntering dandy in the modernized world became the passive cultural interpreter of the grand era. The dandy aesthetics was also a product of this era; the key creative transformation was manifested in the “language” produced in texts translated by those who identified themselves as interpreters and who had internalized their tradition. An analysis of the dandy aesthetics in Sanyu’s painting could perhaps begin with the Eastern calligraphic lines in his many nude sketches, and in the interrelationship between Eastern and Western painting media and concepts that the artist had internalized. From Sanyu’s experimentation with techniques to his practice of artistic styles, we can ultimately see a cross-cultural vocabulary of aesthetics and the remnants of modern history in Sanyu’s work.

The Grande Chaumière Period: Color and Line Experiment

Established in 1902, the Académie de la Grande Chaumière is a non-academic art school in Montparnasse of Paris. The school was founded in a spirit that was an antithesis to the strict painting guidelines of the traditional art school, emphasizing openness, freedom, and innovation in the study of painting. It was here that Sanyu developed his unbridled sketching techniques. We can find a glimpse into Sanyu’s life in Paris as a new arrival in descriptions by his cohort Wang Jigang: “… Sanyu would bring along a blank notebook and pencils, and sit in cafés. He enjoyed observing men and women at adjacent tables, and would immediately begin sketching if he saw someone who stood out from the crowd. This was his extracurricular activity and self-study. … Sometimes if money did not arrive from home and he was short, he would gnaw on dry bread and drink tap water. The only thing of value, his camera, spent a lot of time at the pawnshop; or he would ask me for a loan of hundreds of thousands. When money did arrive from home he would repay and reclaim. … He was beautiful and debonair, impeccably dressed, played the violin and tennis, and was great at billiards. Apart from these things he had no time for cigarettes or alcohol, didn’t dance and didn’t gamble. The love of his life was nature; he was an elegant gentleman."[1] At that time Sanyu, an observer dressed in modern clothes strolling through Paris, explored this modernized city and the people in it. In these aimless leisurely ambles, he caught a glimpse of the ephemerality and happenstance of modern life.

In addition to his practice in Western painting at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, Sanyu often hired models for his quick sketch studies. In his collected writings Tidbits from Paris, Xu Zhimo writes of Sanyu’s obsession with the beauty of the female form, where the artist was quoted, “I cannot live one day without a naked woman lying in front of me to soothe and satisfy my lustful eyes."[2] Pang Xunqin first visited Sanyu’s studio at the end of 1926, and wrote in his memoir That Was How It All Came Through, “In one corner of the room was a pile of his quick sketches, which were all portraits and the human form. Some were drawn with fountain pens, but the majority were line sketches done with the ink brush. His line sketches are very distinctive."[3] He also mentioned, “Personally, I think his lines are more spirited than Tsuguharu Foujita, but Foujita was very famous in Paris at the time, while Sanyu was virtually unknown.”

The earliest dated work of Sanyu is an ink-and-color rendition of peonies on paper, with the ubiquitous peony from Chinese traditional painting as its subject, using the mogu, or boneless, technique to express color and line, and a rendering method to portray the peony’s silhouette. His skillful Chinese ink painting techniques are revealed in his early paintings in Paris. Sanyu’s dexterity in Chinese traditional painting was mentioned, too, in Pang Xunqin’s memoir. “Sanyu had been wonderful at painting flowers and birds in traditional Chinese style. His father was a painter too, and he had a collection of his father’s paintings. After seeing Sanyu’s paintings of birds and flowers, and then looking at his subsequent line drawings of human figures, it is hard to imagine that these paintings came from the same hand."[4] Sanyu used the ink brush for his quick studies during his time at Académie de la Grande Chaumière. The subject of most of these sketches was the female nude. The flowing lines of the brush highlighted the intrinsic nature of this Eastern painting tool. Sanyu outlined the female form by wielding the brush at different speeds to apply varying shades of ink, while using brush and ink with watercolor or with charcoal smears inside the silhouette to create a sense of volume for the limbs. Sanyu was an avid photographer, and often used the wide-angle perspective in his composition, exaggerating the proportions of the woman’s hips and thighs. This was perhaps one of the reasons why he emancipated himself from drawing the female nude in accurate proportions, focusing instead on conceptualization.

The traditions of Chinese ink painting remained visible in Sanyu’s large body of quick studies from this period, reinterpreted through his calligraphic lines in his ink sketches. Upon encountering the concepts of pencils and lines in Western sketches, Sanyu translated the Western precision of line into an Eastern freehandedness. This marked the first stage of transformation in his practice. There was a certain correlation between the rendering of line and the exaggerated proportions in his delineation of the human form. In terms of his watercolors, Sanyu was not in active pursuit of the vibrant color expression popular in Europe at the time, but instead applied the relationship between ink and water in Chinese traditional painting to the palette and spatial sense in his quick sketches of the human form, using light color rendering and charcoal smearing to convey imagery and concept. This application of ink in traditional Chinese style as a contrast to the vivacious color scheme prevalent in the European art circle marked the second stage of transformation in Sanyu's practice. Delving deeper into the foundations of painting, Sanyu had been applying Eastern media to emulate Western painting concepts, and progressed toward an integration of Western media and traditional Chinese aesthetics, until his living conditions were affected by the Great Depression in 1929.

Pink Period: Conceptual Realization

When the Great Depression took place in 1929, Sanyu’s previous sans soucilifestyle encountered steep challenges. In the absence of financial support from home, he was compelled to collaborate with art dealers and collectors, but this was what repulsed Sanyu the most. As Pang Xunqin mentioned in his memoir, “So many times I witnessed him being surrounded by people who wanted to buy his paintings, but he would give the paintings away and refuse those people's money. I don’t know how many times the dealers came for his paintings, and he dismissed them. He even warned me, 'Don’t trust the dealers."[5] However, this revealed the ingrained emotional fetters that confined Chinese artists of that era as they encountered the long-existing art market system of the West. This cultural difference, more than simply an embodiment of the attitude of the Chinese literati, also reflected how Sanyu grappled with the anxieties of modern life amidst overwhelming changes in his living conditions. The dizzying changes in his previously carefree life and the accompanying tension unveiled Sanyu’s continuous struggle for the next three decades.

Anxiety about modernization inspired Sanyu's conscious and liberal approach to art making. This anxiety was more than about earning a living; it also lay in his adherence to the subjectivity of his own culture, for instance, in his literati attitude as he grappled with capitalism, or in his hopeful persistence in going against the artistic trends. This is clear in Sanyu’s discussion of his own aesthetic perspective in an interview with French author Pierre Joffroy, published in Parisien Libéréon December 25, 1946: “La peinture européenne est comme un riche festin où il y a des rôtis, des fritures, toutes sortes de viandes de forme et de couleur variées. Quant à mes toiles, si vous voulez, ce sont des légumes et des fruits, des salades aussi, qui peuvent servir à vous reposer de vos goûts habituels en peinture."[6] (The paintings of Europe can be described as an elaborate meal, consisting of barbecue, fried foods, and meat of all kinds. My work is akin to vegetables, fruit, or salad, which help shape and change the way that people appreciate paintings.) At the same time, Sanyu justified his own simple, unadorned style: “La façon de peindre des modernes, dit-il, est une certaine façon de tricher avec les couleurs; je ne triche pas; je ne puis donc être un peintre comme on l’entend de nos jours..."[7] (Contemporary painters deceitfully always paint with many colors. I don’t deceive, so I am not considered as one of the more popular painters....) Here Sanyu’s confidence and tenacity in his own painting can be clearly discerned. He was keenly aware of the invisible hand of capitalism behind the diversity of the art world, but still maintained a certain “stance” in the torrents of modern life. By maintaining a lucid self in a time of cacophony and mass commodification, Sanyu distilled an independent, prudent, and unyielding personality from the anxiety about cultural subjectivity and self-actualization, while resonating with the state of simplicity and self-cultivation that the Chinese literati longed for in times of chaos.

The year 1929 was the start of what was perhaps Sanyu’s most prolific period. That year, Sanyu began collaborating with the famed French art dealer and collector Henri-Pierre Roché(1879–1959). Roché’s collection focused on notable members of the School of Paris, including Pablo Picasso (1881–1973), Georges Braque (1882–1963), Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920), and Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). Although their collaboration was brief, Rochékept records of his dealings and transactions with Sanyu between December 1929 and November 1932. According to the list of Sanyu’s works collected by Roché, with the exception of one sketch on paper, a total of 109 pieces were all oil paintings.[8]

An artistic transformation and evolution unfolded in the ways Sanyu segued between Western media and traditional Chinese aesthetics, and this is especially discernible in his oil paintings from this period. Firstly, in the simple palette of black, white, and pink. Secondly, after the base color is thoroughly dry, a second layer of background color is applied using the flying white, or feibai, calligraphy technique. Finally, a dry brush is used to tease out and recreate objects and a spatial sense. The specific use of the three colors was Sanyu's common color scheme prior to the 1940s, which was simple and quite often pink. Hence, it is often referred to as his “Pink Period.” Sanyu’s application of the flying white technique is obvious in his works from this period. In traditional Chinese calligraphy, flying white creates a sense of rhythm through the strength of the brush as well as the drybrush technique that renders streaks and specks of ink on paper; a classical manifestation of the real and imaginary in traditional Chinese painting. A culminating moment in Sanyu’s oil practice is when he uses a dry brush to tease out lines against the flying-white background; these lines slice open the still-wet second layer of background color. The brushwork, similar to chisel marks, often reveals fortuitous traces of timewornness, underscoring the solemnity of oils. With the flying-white background devoid of the Western linear perspective, Sanyu’s paintings seem even more subdued and two-dimensional, especially when the paintbrush moves unwieldily through oil paints, brushstrokes falling in syncopated cadence, penetrated by a palpable sense of vicissitudes.

At the time, Fauvism, Cubism, and Neo-Expressionism were the predominant styles of painting in Europe.Surrounded by artistic trends that favored vibrant colors, precise composition, and Eurocentrism, Sanyu’s tricolor palette and two-dimensional flying-white background was deemed lacking a sense of volume, devoid of vivacious colors and contrast, essentially regarded as decorative work. This is also why despite being immersed in European modernist art for almost forty years, he continued to adhere to the traditional artistic styles, subject matter, and aesthetics of the Chinese literati.Sanyu's modernist vocabulary is an amalgamation of Western styles and Chinese aesthetics, an equilibrium between self and the existing order. Straddling cultural boundaries, his creative spirit serves as a portal into a world where traditional Chinese aesthetics nurtured in a Western modern art milieu gave rise to artistic ingenuity. It is such ingenuity that foregrounds Sanyu in Chinese modern art history.

Hidden Blossoms

If the dandy aesthetics is a form of cultural creation through the self and the Other in the modernized world, then being a dandy implies being able to roam through the cultural realm. Like a mirror, the dandy reflects the diversity of the times, the city, and the people, simultaneously internalizing his experiences in the process of “self completion” and embodying an amalgamated existence of the Other and the self through profound visual aesthetics. In confronting the uncertainty of modernization, Sanyu engaged in a self-introspection, looking for opportunities to reinvent himself in this volatile life. Perhaps just as how French poet Baudelaire describes Mr. G in Le Peintre de la vie moderne:

“Ainsi il va, il court, il cherche. Que cherche-t-il? A coup sûr, cet homme, tel que je l’ai dépeint, ce solitaire doué d’une imagination active, toujours voyageant à travers le grand désert d’hommes, a un but plus élevé que celui d’un pur flâneur, un but plus général, autre que le plaisir fugitif de la circonstance. Il cherche ce quelque chose qu’on nous permettra d’appeler la modernité; car il ne se présente pas de meilleur mot pour exprimer l’idée en question.”(And so, walking or quickening his pace, he goes his way, for ever in search. In search of what? We may rest assured that this man, such as I have described him, this solitary mortal endowed with an active imagination, always roaming the great desert of men, has a nobler aim than that of the pure idler, a more general aim, other than the fleeting pleasure of circumstance. He is looking for that indefinable something we may be allowed to call ‘modernity,’ for want of a better term to express the idea in question.)

The exhibition Sanyu’s Hidden Blossomsinstantiates the aesthetic vocabulary of Sanyu’s modernist painting. The twigs and shoots that uphold the blooms in Sanyu’s numerous paintings of flowers in vases from his Pink Period serve as a starting point in understanding Sanyu's art through his use of line. In the exhibition title, “hidden” refers to the zeitgeist of that era captured through Sanyu's brushwork rendered in thick oils; “blossoms” conjures Sanyu's life in the Fleur de Paris, as well as hinting at the Chinese heritage that had cradled this modernist pioneer, allowing Eastern and Western aesthetics to coalesce in his painting against a transcultural backdrop. If Sanyu’s dandyism was a ray of light in the midst of catastrophic changes in the world at that time, the dandies that gradually migrated to Tokyo and Shanghai opened new windows onto the literary world and enriched a nascent global modernization.What is the significance of the many floral still-lifes and nude sketches from Sanyu’s Pink Period — recurrent motifs so often deemed monotonous and dull? Perhaps here, form, subject, or content isn’t of great importance. For instance, the copious chrysanthemums in over a hundred paintings, attest to the fact that the silhouette of the chrysanthemum morphs into a private realm where Sanyu abandons himself to the wielding of the paintbrush. The paintbrush making its way through the viscous oil paint leaves traces reminiscent of a golden era, faintly glimmering with Sanyu's creative spirit.

Treading the line between Western modernity and cultural tradition, Sanyu bore witness to a burgeoning new era, and instantiated the dandy aesthetics in a cross-cultural modern milieu. His artistic expression that amalgamates the disparate values and aesthetics of the East and the West underscores not only Sanyu’s inclusiveness in those crazy years, but also his compromise and reinvention in shaping his aesthetic vocabulary. Eventually, the viewer might recognize the profound creative aesthetics in Sanyu's work, transcending cultural boundaries, elitism, and popular culture, allowing us a chance to grasp the poetics in aesthetics and history.

[1]Sanyu, Antoine Chen, Artist Publishing, September 30, 1995, p. 15.

[2]Tidbits from Paris, Xu Zhimo, Crescent Moon Publishing, Shanghai, January 1930, pp. 25-26.

[3]Jiu Shi Zhe Yang Zou Guo Lai De(literal translation: That Was How It All Came Through), Pang Xunqin, Joint Publishing, Beijing, June 1988, p. 83.

[4]Ibid., p. 84.

[5]Ibid., p. 84.

[6]Inventeur de ‘l’essentialisme’ San-Yu peintre chinois de Montparnasse,” Pierre Joffroy, Parisien Libéré, December 25, 1946.

[7]Ibid.

[8]Sanyu: Catalogue Raisonné,Oil Paintings, Yageo Foundation and Lin & Keng Art Publications, 2001, p. 48 and pp. 166-179.

-

Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandy

SANYU’S HIDDEN BLOSSOMS: THROUGH THE EYES OF A DANDY Continue -

Artists’ Perspective| Through the Eyes of Chen, Ching-Yuan

Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandy Continue -

Artists’ Perspective| Through the Eyes of Yao Jui-Chung

Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandy Continue -

Artists’ Perspective| Through the Eyes of LIN JU

Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandy Continue -

Trailer| Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandy

Sanyu solo exhibition Continue

-

Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandy

SANYU’S HIDDEN BLOSSOMS: THROUGH THE EYES OF A DANDY Continue -

Artists’ Perspective| Through the Eyes of Chen, Ching-Yuan

Sanyu’s Hidden Blossoms: Through the Eyes of a Dandy Continue

Related artist

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.