Xiang Nai Er: Su Meng-Hung Solo Exhibition

Xiang Nai Er: Su Meng-Hung Solo Exhibition

- Press Release

- Works

- Installation Shots

- Publications

- Events

-

Share

- X

- Tumblr

“This series of works is, and isn’t about Chanel/Xiang Nai Er (Chanel in Chinese transliteration).”

A mosaic collage of pearl shells in the shape of Chinese flowers and birds inlaid in antique lacquered ebony, against a resplendent landscape of ivory, jade, enamel, gold, and silver, enshrouds the viewer in a magnificent and delicate Eastern atmosphere — the ebony lacquer screen that enchanted Ms. Coco Chanel all her life. Fascinated by the mysterious aura of this Chinese traditional craft, Ms. Chanel turned it into her renowned source of inspiration. Ever since then, the still life and landscape depicted on the ebony screens have been transformed into prevalent Eastern cultural symbols. Embroidered onto exquisite fabric in haute couture, reincarnated as luxury jewelry design, these symbols redefined by Chanel’s elegant and classical style, garner international attention.

Chinese ebony screens have a non-Chinese nickname in the Western world: “coromandel screen,” referring to the Coromandel Coast of southeastern India, a colonial trading port from which Chinese furniture goods were once shipped to Europe in the late 17th century. Even today, this nickname still faintly exudes the ambience of the Marco Polo era, conjuring an exotic silhouette obscured by time. The imagery on the ebony screen — vivid flowers and birds against idyllic landscapes — transmutes the Western notions of China into a pan-Eastern sentiment that is now independent of Chinese culture.

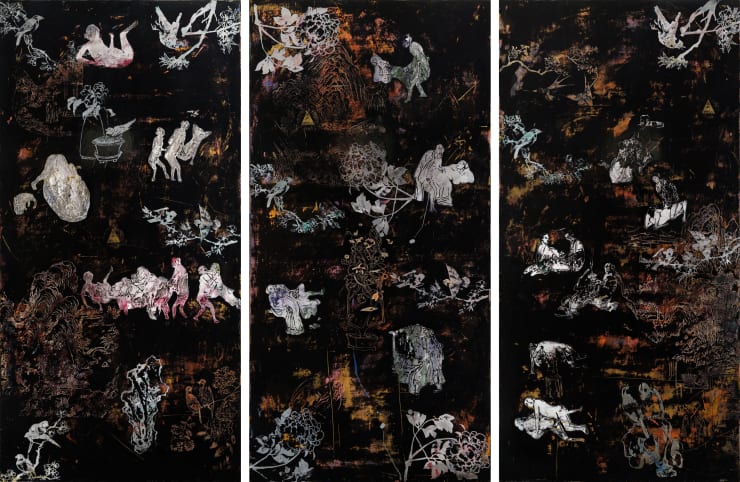

This has inspired Su Meng-Hung’s latest painting series “Xiang Nai Er” (2018–2019). For Su, if anything after being translated could leave behind either a stunning signifier, or an absurd signified because of a romantic misunderstanding, this would come awfully close to what art is in reality. Just like the brand Chanel evokes distinct imagery after being conveyed through different media outlets and appropriated by different artists, the name “Xiang Nai Er” no longer belongs to Chanel. Instead, the name metamorphoses into an organic term that reconfigures Chanel’s every cultural connotation. In response, Su sees Ms. Chanel’s collection of ebony lacquer screens as his muse, fusing abstract expressionism with automatism manifested in splashed ink landscape. He renders the imagery effaced and buried beneath layers of thick paint, and the surface would be sanded to allow the image to re-emerge, yet leaving lines or clusters of paint that have survived the attrition as the visual aesthetics of the painting.

The interspersed images are adopted from eminent Chinese classical painting technique book Manual of the Mustard Seed Garden, Chinese literary masterpiece Dream of the Red Chamber, and the erotic illustrations from Chinese literary classic The Golden Lotus. Accordingly, Su’s work exhibits a dualistic sensory and material character. The artist deliberately juxtaposes diametric opposites — nothingness and splendor, secularity and religion, integrity and fragmentation, Eastern tradition and Western classics — to challenge fixed dichotomies, reading them together to discover new knowledge and expand the possibilities of wider reference.

“In crafting the sensory and material character of his work, Su develops an ambiguous visual style, often eluding the true implications of his referents — as seen in the still life paintings, flower and bird paintings, and the erotic paintings referenced by him — by detaching and fragmenting them,” architect and writer Roan Ching-Yueh comments on Su’s work thus. “By re-contextualizing these symbols, he dissociates them from their original historical and cultural significances. The artist arranges them into a naive, flamboyant scene, facing society with vulgar symbolic gestures and a sense of confrontation and ridicule.”

“Xiang Nai Er” is a series of paintings that embeds the function and meaning of poster and display in painting. The series comprises the artist’s years-long affinity for visual motifs that have been stylized and modeled into uniform, grotesque imagery, as well as an incorporation of Western expressionism and Zhang Daquian-esque performative techniques of splashed ink landscape. Chanel no longer belongs to Chanel. Just like to whom art belongs? Despite that the “Xiang Nai Er” series is not about Chanel, it is steeped in the profound implications that the brand has etched into the contemporary psyche. Su Meng-Hung begins with traditional but non-classical imagery, using stylized, uniform motifs as visual reference with a new creative dimension. His latest solo exhibition is simultaneously a direct response to contemporary social phenomena, and a spiritual calling with redemption expectations for the classical.

Related artist

This website uses cookies

This site uses cookies to help make it more useful to you. Please contact us to find out more about our Cookie Policy.